Oreille d'éléphant géante

(Alocasia macrorrhizos)

0 pour les parties aériennes et -3/-4 (durant une courte période) pour les racines

Une très grande herbe. Une plante de la famille taro. Il a un tronc robuste et dressé atteignant 4 m de haut. Cela a des feuilles verticales en forme de flèche. Les feuille ... (traduction automatique)

→suite

Oreille d'éléphant géante

Note alimentaire ![]()

![]()

![]()

Note médicinale ![]()

Une très grande herbe. Une plante de la famille taro. Il a un tronc robuste et dressé atteignant 4 m de haut. Cela a des feuilles verticales en forme de flèche. Les feuilles ont des lobes ronds en bas. Les feuilles sont coriaces et sont souvent ondulées sur le pourtour. Les veines secondaires ne sont pas proéminen... (traduction automatique) →suite

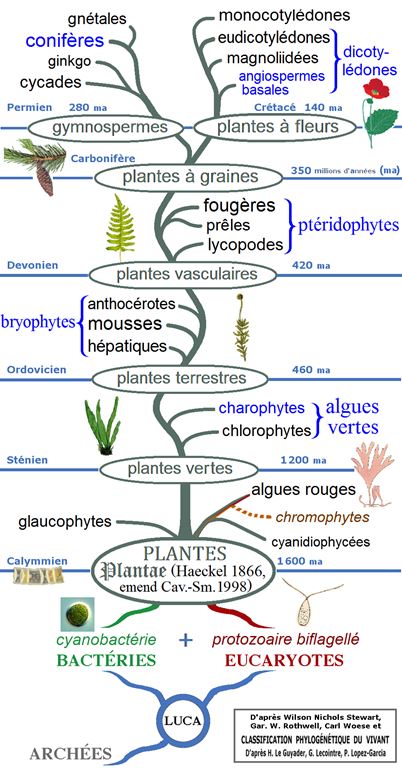

Classification

- Classique : en haut de l\'écran, sous le coeur.

- Phylogénétique :

- Clade 4 : Angiospermes ;

- Clade 3 : Monocotylédones ;

- Ordre APN : Alismatales ;

- Famille APN : Araceae ;

Illustration : cet arbre phylogénétique des plantes montre les principaux clades et groupes traditionnels (monophylétiques en noir et paraphylétiques en bleu).

Dénominations

✖- Nom botanique : Alocasia macrorrhizos (L.) G. Don (1839)

- Synonymes français : taro géant, alocasie, alocasia, alocasie géante, alocasie à grande racine, alocasie à grosse racine, ape (Hawaï), oreille d'éléphant, songe caraïbe, songe papangue, grande tayove, taro

- Synonymes : Alocasia alba Schott 1852 (nom accepté et espèce différente/distincte, selon TPL), Alocasia crassifolia Engl. 1920 (synonyme d'Alocasia alba Schott 1852, selon TPL), Alocasia indica (Lour.) Schott 1854, Alocasia macrorrhiza (L.) Schott 1852, Arum indicum Lour. 1790, Caladium glycirrhizza (synonyme selon DPC), Colocasia indica (Lour.) Kunth 1841 ;

Dont basionyme : x ; - Noms anglais et locaux : ape, cunjevoi, giant alocasia, giant taro, pai, Alokasie (de)

Description et culture

✖- dont infos de "FOOD PLANTS INTERNATIONAL" :

Description :

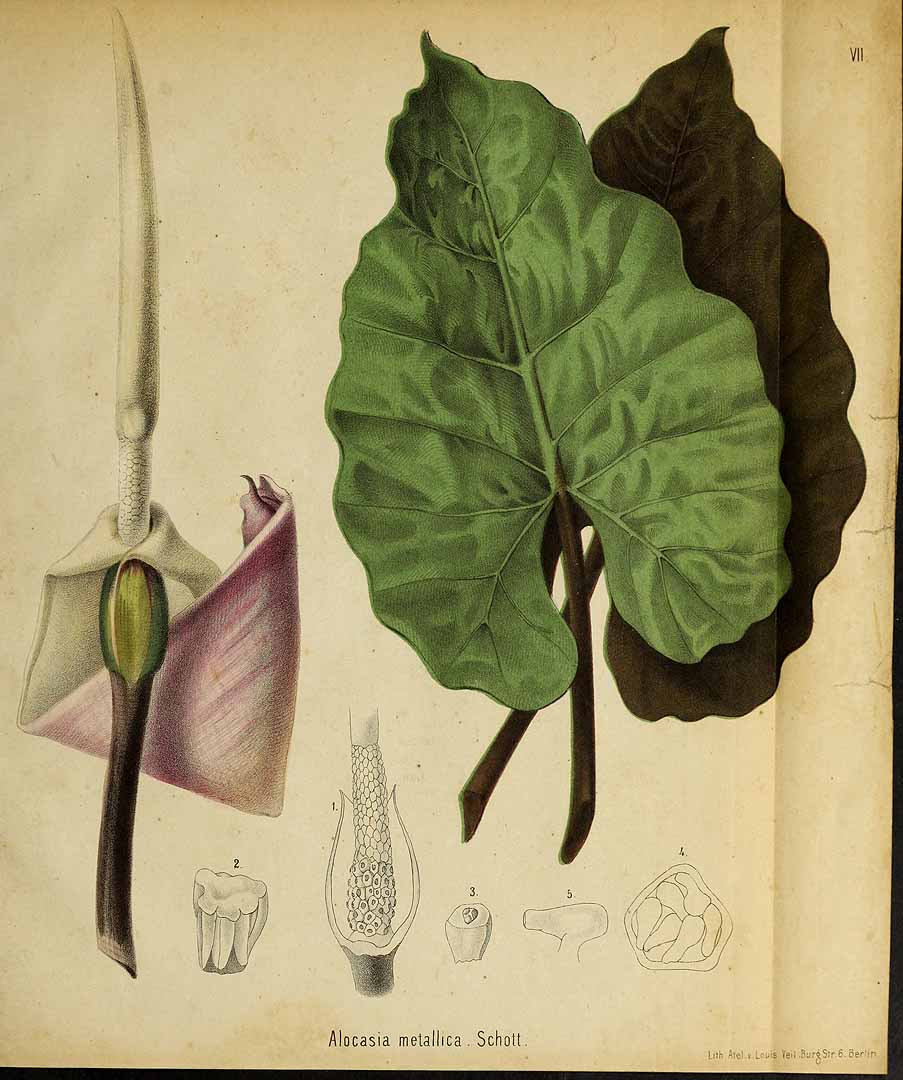

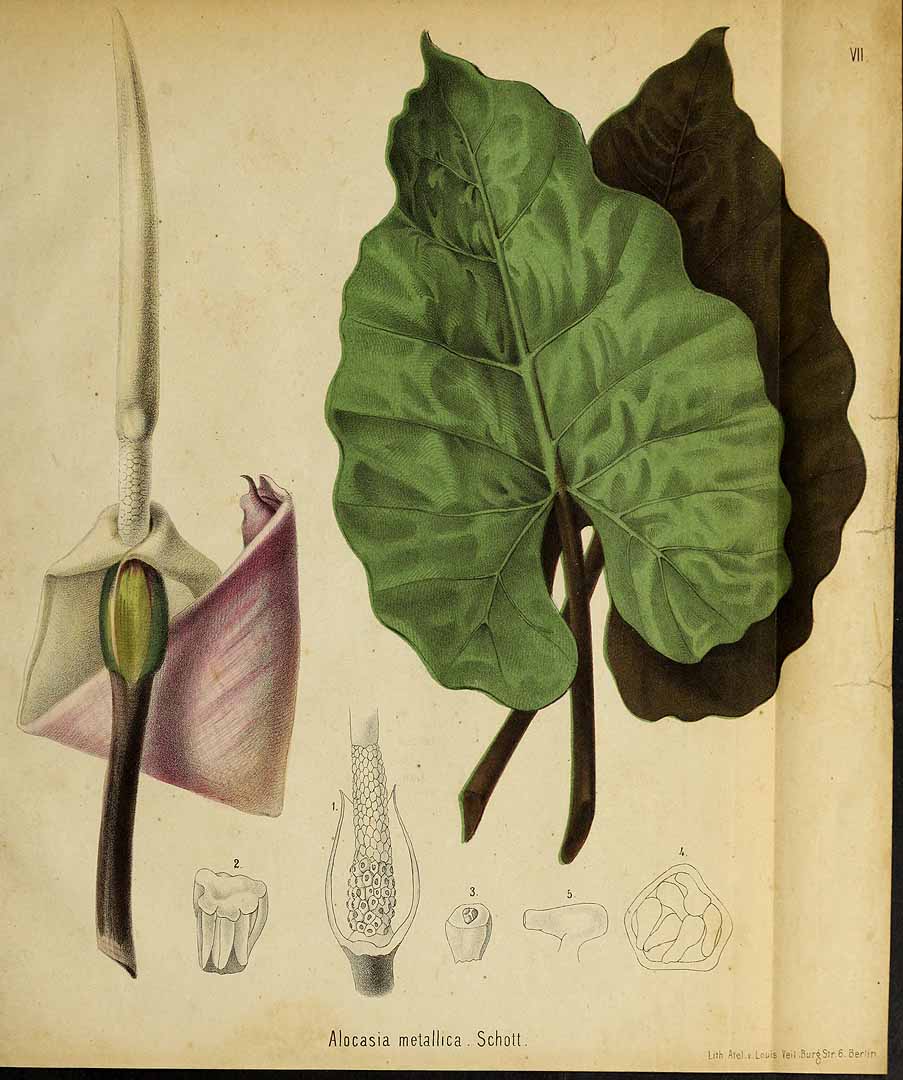

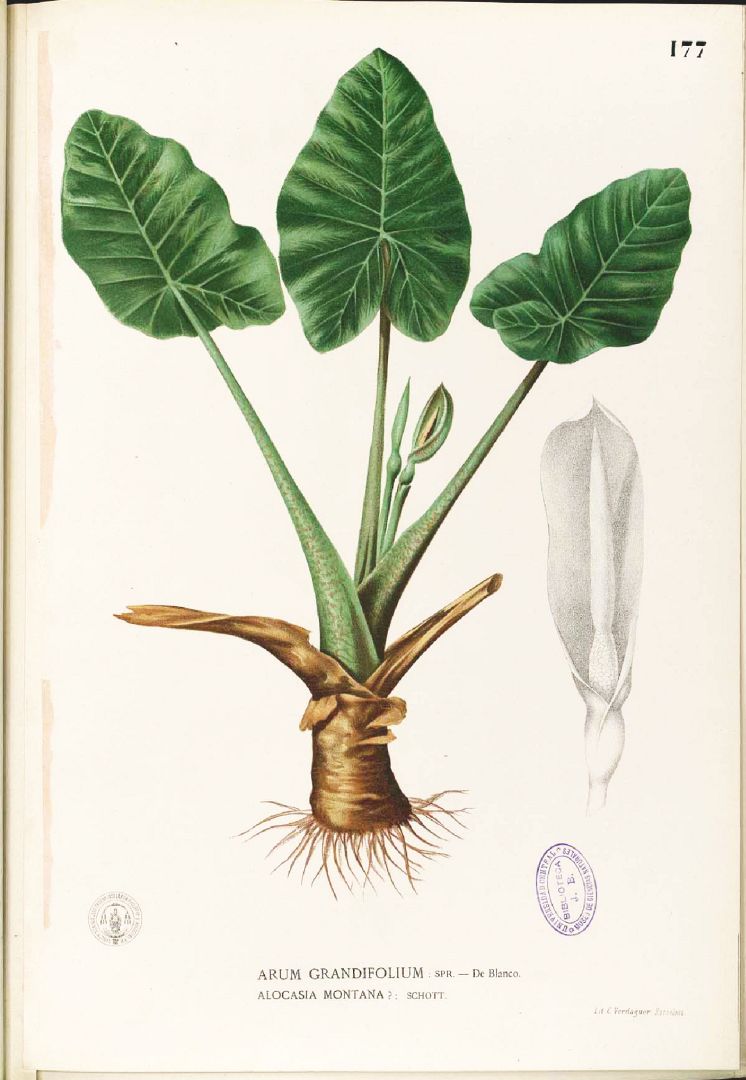

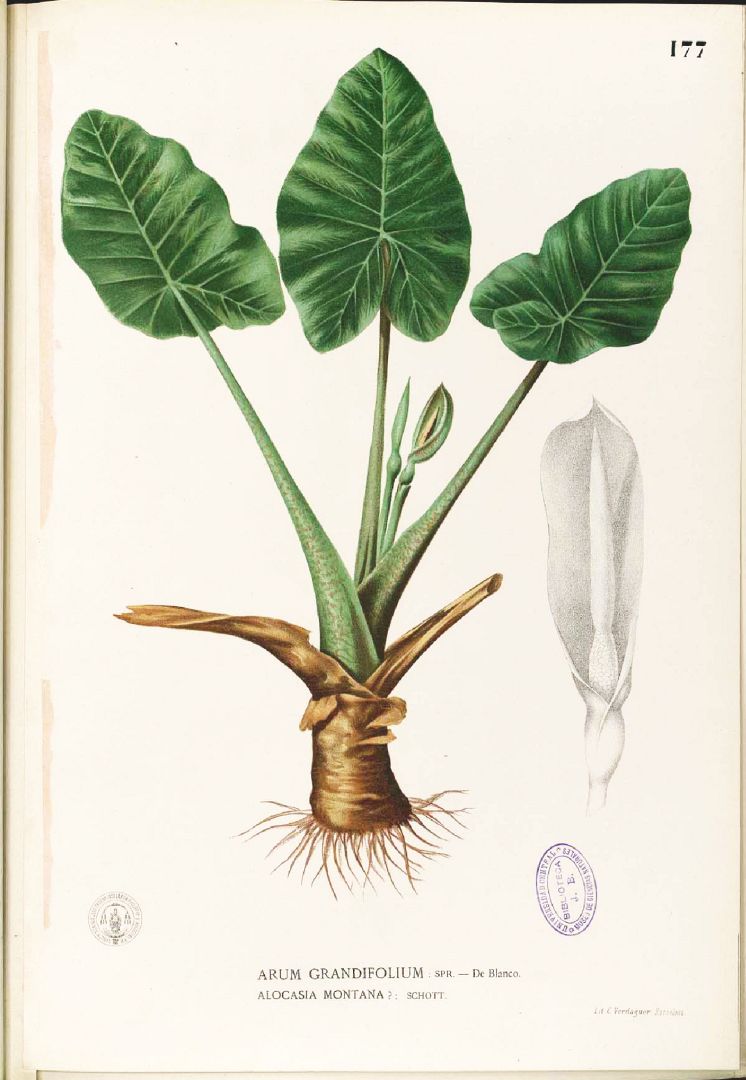

Une très grande herbe. Une plante de la famille taro. Il a un tronc robuste et dressé atteignant 4 m de haut. Cela a des feuilles verticales en forme de flèche. Les feuilles ont des lobes ronds en bas. Les feuilles sont coriaces et sont souvent ondulées sur le pourtour. Les veines secondaires ne sont pas proéminentes. Le limbe des feuilles peut mesurer de 1 à 1,2 m de long. La structure feuillue autour de la fleur est jaune dans la partie supérieure. Il forme un capuchon et tombe lorsque la fleur s'ouvre. Les fruits sont des baies rouge vif. Le bulbe est grand, souvent courbé et au-dessus du sol. Il a souvent de petits bulbes sur le côté. Les fibres brunes de la base des feuilles pendent souvent de la tige. Les feuilles et les pétioles contiennent des cristaux piquants{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique).

Original : A very large herb. A taro family plant. It has a stout erect trunk up to 4 m tall. This has upright leaves which are arrow shaped. Leaves have round lobes at the bottom. The leaves are leathery and are often wavy around the edge. The secondary veins are not prominent. The leaf blade can be 1-1.2 m long. The leafy structure around the flower is yellow in the upper section. It forms a hood and drops off as the flower opens. The fruit are bright red berries. The corm is large, often curved and above the ground. It often has small cormels at the side. Brown trailing fibres of the leaf bases often hang from the stem. The leaves and petioles contain stinging crystals{{{0(+x).

Production :

Des cormes de 8,5 à 40 kg ont été récoltées sur des plantes individuelles d'âge inconnu. Le temps de maturité est d'environ 12 mois, mais les plantes sont souvent laissées pendant 2-3 ans{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique).

Original : Corms of 8.5 to 40 kg have been harvested from individual plants of unknown age. The time to maturity is about 12 months but plants are often left for 2-3 years{{{0(+x).

Culture :

Le sommet du corme principal est planté. Les petits bulbes ronds peuvent être plantés, mais tardent à mûrir. Un espacement de 1,2 x 1,2 m convient. Étant donné que le taro géant met plus d'un an à être prêt à être récolté, il finit souvent par pousser dans un ancien jardin sans trop de soin ni de désherbage, jusqu'à ce que le propriétaire veuille le récolter. La bouche peut être irritée par la mastication de parties de plantes mal cuites en raison de produits chimiques appelés oxalates. Le taro géant contient de petits cristaux d'oxalate de calcium en forme d'aiguille dans les tissus. Il est nécessaire de les retirer pendant la préparation et la cuisson. La méthode d'épluchage est importante. Normalement, certaines femmes qui sont particulièrement expérimentées dans le pelage font ce travail. De plus, le corme de taro est souvent laissé à flétrir pendant une semaine après sa récolte et avant son utilisation. Aussi pour aider à éliminer certains des cristaux, la tige est cuite pendant une longue période ou bouillie dans plusieurs changements d'eau. Il est également important d'utiliser la bonne variété de taro géant car les variétés cultivées dans les jardins contiennent moins de produits chimiques que les sauvages{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique).

Original : The top of the main corm is planted. The small round cormels can be planted, but are slow to mature. A spacing of 1.2 x 1.2 m is suitable. Because the giant taro takes more than a year to be ready to harvest, it often ends up left growing in an old garden site without much care or weeding, until the owner wants to harvest it. The mouth can be irritated by chewing improperly cooked plant parts due to chemicals called oxalates. Giant taro contains small needle-like calcium oxalate crystals in the tissues. It is necessary to remove these during the preparation and cooking. The method of peeling is important. Normally some ladies who are especially experienced at peeling do this job. Also the taro corm is often left to wilt for a week after it is harvested and before it is used. Also to help remove some of the crystals, the stem is baked for a long time, or boiled in several changes of water. It is also important to use the right variety of giant taro because the kinds grown in gardens have less of the chemical than wild ones{{{0(+x).

Consommation (rapports de comestibilité, parties utilisables et usages alimentaires correspondants)

Consommation (rapports de comestibilité, parties utilisables et usages alimentaires correspondants)

✖

Racine (cormes (rhizomes(27(+x)µ épaissis en tubercules écailleux{{{(dp*)) cuit27(+x) (généralement(dp*) dans plusieurs eaux{{{27(+x)) [nourriture/aliment : légume{{{2(dp*),27(+x), féculent (amidon/fécule){{{2(dp*)]) comestible.(1*)

Détails : Plante importante localement, très cultivée dans les pays tropicaux.{{{27(+x)

Partie testée :

rhizome{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique). Original : Rhizome{{{0(+x)| Taux d'humidité | Énergie (kj) | Énergie (kcal) | Protéines (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 63.2 | / | / | 3.3 |

| Pro- vitamines A (µg) |

Vitamines C (mg) | Fer (mg) | Zinc (mg) |

| / | / | / | / |

Risques et précautions à prendre

Risques et précautions à prendre

✖

néant, inconnus ou indéterminés.

Galerie(s)

✖Autres infos

✖dont infos de "FOOD PLANTS INTERNATIONAL" :

Statut :

C'est un légume cultivé commercialement. Ce taro n'a d'importance locale que dans certaines zones côtières et îles de Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée, par exemple Rabaul, Namatanai. Il est important dans plusieurs îles du Pacifique et au Sri Lanka{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique).

Original : It is a commercially cultivated vegetable. This taro is of local importance only in some coastal areas and islands of Papua New Guinea e.g. Rabaul, Namatanai. It is important in several Pacific Islands and Sri Lanka{{{0(+x).

Distribution :

Une plante tropicale. Il est largement répandu dans les zones humides ouvertes et le long des cours d'eau et dans certains types de forêts humides. La plante pousse à l'état sauvage du niveau de la mer jusqu'à 2600 m d'altitude sous les tropiques. Le taro géant est une plante tropicale et ne poussera pas bien en dessous de 10 ° C. Il nécessite une pluviométrie bien répartie et ne tolère pas la sécheresse. Même s'il pousse le long des berges des ruisseaux, il ne peut tolérer un sol gorgé d'eau. Il n'est utilisé comme nourriture que dans quelques zones côtières. Les formes sauvages couramment observées en croissance sont amères et non utilisées. Cela ne marche pas bien sur les atolls. Il convient aux zones de rusticité 11-12{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique).

Original : A tropical plant. It is widely distributed in open wetlands and along streams and in some types of humid forest. The plant grows wild from sea level up to 2600 m altitude in the tropics. Giant taro is a tropical plant and will not grow well below 10°C. It requires a well distributed rainfall and does not tolerate drought. Even though it grows along creek banks it cannot tolerate waterlogged soil. It is only used as food in a few coastal areas. Wild forms commonly seen growing are bitter and not used. It does not do well on atolls. It suits hardiness zones 11-12{{{0(+x).

Localisation :

Afrique, Samoa américaines, Asie, Australie, Bangladesh, Cambodge, Îles Caroline, Amérique centrale, Chuuk, Îles Cook, Cuba, République dominicaine, Timor oriental, Île de Pâques, Fidji, Polynésie française, FSM, Guam, Guyanes, Haïti, Hawaï, Himalaya, Inde, Indochine, Indonésie, Jamaïque, Japon, Kiribati, Kosrae, Laos, Madagascar, Malaisie, Maldives, Mariannes, Marquises, Îles Marshall, Micronésie, Myanmar, Nauru, Nouvelle-Calédonie, Inde du nord-est, Amérique du Nord, Pacifique, Pakistan, Palau, Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée, PNG, Philippines, Pohnpei, Porto Rico, Rotuma, Samoa, Sao Tomé-et-Principe, Asie du Sud-Est, Singapour, Îles Salomon, Amérique du Sud, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Tahiti, Taiwan, Thaïlande, Timor-Leste, Tokelau, Tonga, Truk, Tuvalu, USA, Vanuatu, Vietnam, Afrique de l'Ouest, Antilles, Yap, {{{0(+x) (traduction automatique).

Original : Africa, American Samoa, Asia, Australia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Caroline Islands, Central America, Chuuk, Cook Islands, Cuba, Dominican Republic, East Timor, Easter Island, Fiji, French Polynesia, FSM, Guam, Guianas, Haiti, Hawaii, Himalayas, India, Indochina, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Kiribati, Kosrae, Laos, Madagascar, Malaysia, Maldives, Marianas, Marquesas, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Myanmar, Nauru, New Caledonia, Northeastern India, North America, Pacific, Pakistan, Palau, Papua New Guinea, PNG, Philippines, Pohnpei, Puerto Rico, Rotuma, Samoa, Sao Tome and Principe, SE Asia, Singapore, Solomon Islands, South America, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Tahiti, Taiwan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tokelau, Tonga, Truk, Tuvalu, USA, Vanuatu, Vietnam, West Africa, West Indies, Yap{{{0(+x).

Notes :

Il existe environ 60 à 70 espèces d'Alocasia{{{0(+x) (traduction automatique).

Original : There are about 60-70 Alocasia species{{{0(+x).

Rusticité (résistance face au froid/gel, climat)

✖0 pour les parties aériennes et -3/-4 (durant une courte période) pour les racines

Liens, sources et/ou références

✖Sources et/ou références :

5"Plants For A Future" (en anglais) ;

dont classification : "The Plant List" (en anglais) ; 2"GRIN" (en anglais) ;

dont livres et bases de données : 27Dictionnaire des plantes comestibles (livre, page 19, par Louis Bubenicek) ;

Recherche de/pour :

- "Alocasia macrorrhizos" sur Google (pages et

images) ;

TROPICOS (en anglais) ;

Tela Botanica ;

Pl@ntNet ;

Pl@ntUse ;

- "Oreille d'éléphant géante" sur Google (pages, images et recettes) ;

- "Alocasia macrorrhizos" sur Google (pages et

images) ;

TROPICOS (en anglais) ;

Tela Botanica ;

Pl@ntNet ;

Pl@ntUse ;

Sous-espèces, variétes...

✖3 taxons

Espèces du même genre (Alocasia)

✖11 taxons

- Alocasia acuminata

- Alocasia brisbanensis

- Alocasia cucullata (Lour.) G. Don (Taro chinois)

- Alocasia fallax

- Alocasia fornicata

- Alocasia hollrungii

- Alocasia lancifolia

- Alocasia macrorrhizos (L.) G. Don (Oreille d'éléphant géante)

- Alocasia odora (Lindl.) K.Koch (Oreille d'éléphant)

- Alocasia portei

- Alocasia sanderiana

Espèces de la même famille (Araceae)

✖50 taxons (sur 240)

- Acorus calamus L. (Acore odorant)

- Acorus gramineus Sol. ex Aiton

- Aglaonema costatum

- Aglaonema philippinense

- Aglaonema pictum

- Alloschemone inopinata

- Alocasia acuminata

- Alocasia brisbanensis

- Alocasia cucullata (Lour.) G. Don (Taro chinois)

- Alocasia fallax

- Alocasia fornicata

- Alocasia hollrungii

- Alocasia lancifolia

- Alocasia macrorrhizos (L.) G. Don (Oreille d'éléphant géante)

- Alocasia odora (Lindl.) K.Koch (Oreille d'éléphant)

- Alocasia portei

- Alocasia sanderiana

- Amorphophallus abyssinicus

- Amorphophallus albus

- Amorphophallus aphyllus

- Amorphophallus asterostigmatus

- Amorphophallus bhandarensis

- Amorphophallus brevispathus

- Amorphophallus bulbifer

- Amorphophallus commutatus

- Amorphophallus consimilis

- Amorphophallus dracontioides

- Amorphophallus gallaensis

- Amorphophallus glabra

- Amorphophallus gomboczianus

- Amorphophallus harmandii

- Amorphophallus kachinensis

- Amorphophallus konjac K.Koch (Koniaku)

- Amorphophallus konkanensis

- Amorphophallus koratensis

- Amorphophallus krausei

- Amorphophallus lyratus

- Amorphophallus margaritifer

- Amorphophallus muelleri

- Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson (Songe pâté)

- Amorphophallus prainii

- Amorphophallus purpurascens

- Amorphophallus rivieri

- Amorphophallus saraburiensis

- Amorphophallus stuhlmannii

- Amorphophallus sylvaticus

- Amorphophallus titanum

- Amorphophallus variabilis

- Amorphophallus ximengensis

- Amorphophallus yuloensis

- ...