! Nouveau site ici !

Vita > Plantae > Magnoliophyta > Liliopsida > Arales >

Araceae > Colocasia

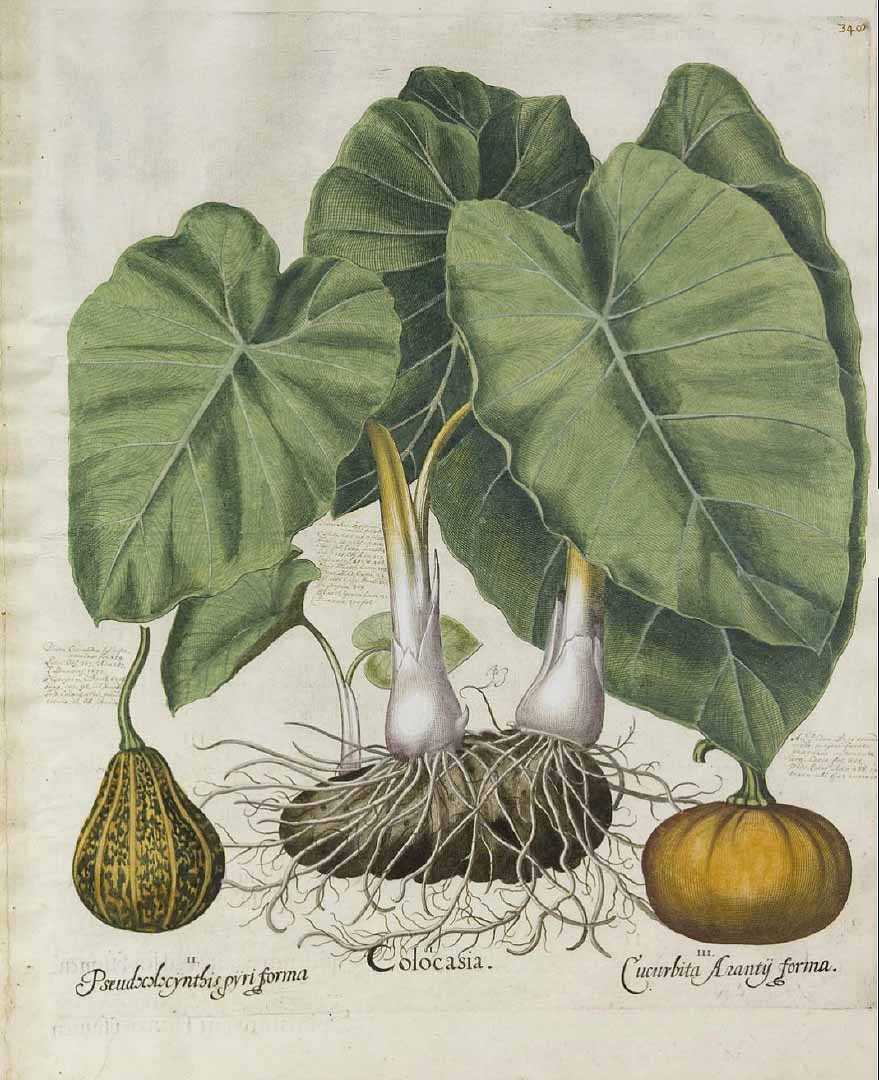

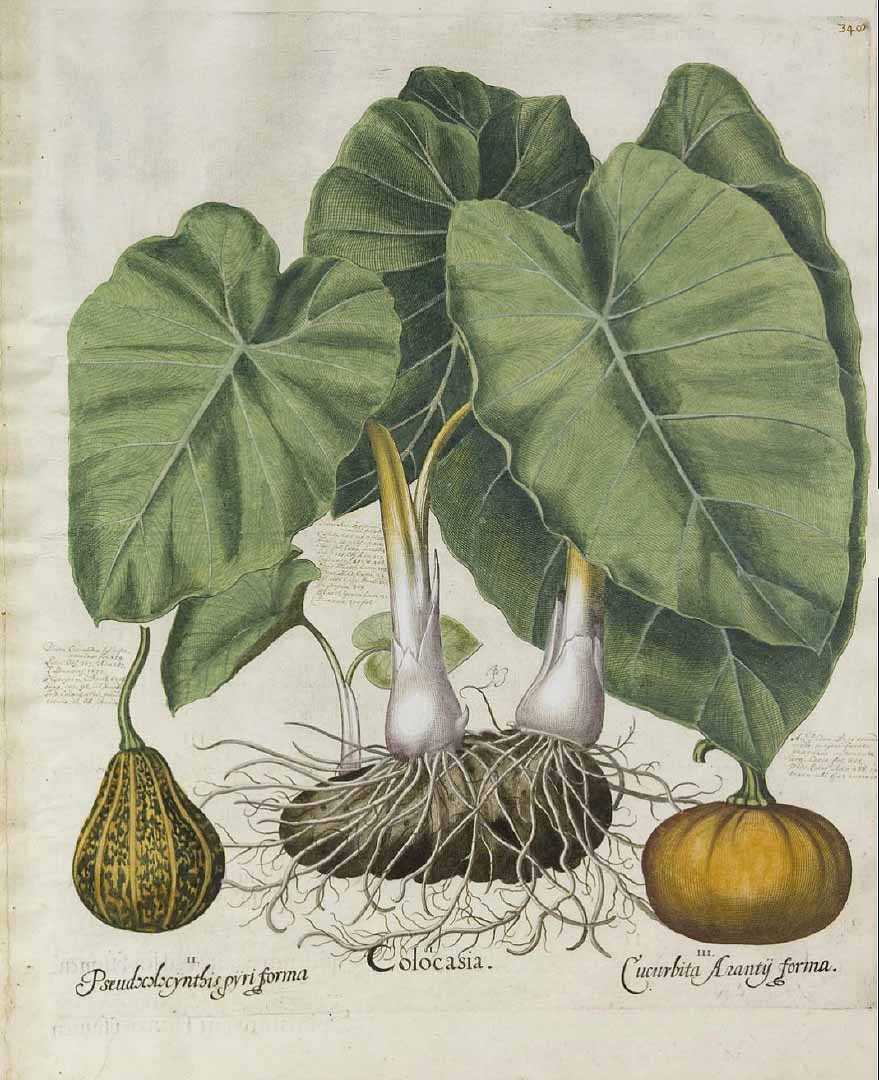

Colocasia esculenta

(Taro)

| ****

| ****

Vita > Plantae > Magnoliophyta > Liliopsida > Arales >

Araceae > Colocasia

Colocasia esculenta

(Taro)

Cette plante a de grandes feuilles plates à l'extrémité des tiges de feuilles verticales. Il pousse jusqu'à 1 m de haut. La tige ou pétiole de la feuille rejoint la feuille vers le centre de la feuille. Le... (traduction automatique)

→suite

⬀

Le  donne accès au menu

donne accès au menu (c'est votre point de repère) 😊 ;

En dessous vous avez la classification, à partir de la vie (Vita, premier rang) jusqu'à la classe au dessus de la plante, dont vous trouvez ensuite le nom scientifique/botanique (latin) puis le nom commun (français), le cas échéant ;

C'est aussi un lien vers la fiche complète (tout comme la ✖, en bas à droite, et le +, en dessous de la description) ;

Vient alors l'illustration (ou ce qui la remplace, en attendant), la comestibilité :

Et en bas

⬂